By Lincoln Roch

Democrat Jillare McMillan talks to an undecided voter outside of their house Saturday, Sept. 28, 2024, in Erie. McMillan entered the House District 19 race in August after incumbent Colorado Rep. Jennifer Parenti, D-Erie, dropped out of the race. (Lincoln Roch, Special to The Colorado Sun)

About six years ago an idea popped into Jillaire McMillan’s head. Maybe someday she’d run for office.

The revelation wasn’t a big shock. In high school, she was voted most likely to be the first female president, a title she’d happily give up to Vice President Kamala Harris this year.

McMillan, a mom of four who lives outside Longmont, had also served as the parent-teacher association president at her kids’ elementary, middle and high schools. In the first weeks of the Trump administration, she joined a Facebook group founded by a lifelong Republican upset by Donald Trump’s disparaging rhetoric. The group, Mormon Women for Ethical Government, quickly grew into a 7,000-member nonpartisan organization that helps women get involved in government. McMillan would end up as its chief of staff.

It made sense McMillan wanted to run. But she figured she’d do it five or 10 years down the road. Then, in late July, her state representative, Democrat Jennifer Parenti, dropped her reelection bid in the waning months of a contentious campaign.

A vacancy committee was announced to choose a new candidate for the party. It was meeting in 10 days, so there was a decision to be made. She decided it was time.

“I just thought maybe I should take advantage of this opportunity to just jump in,” McMillan said.

The district includes the towns of Erie, Firestone, Frederick and Dacono and is made up of a mix of suburban neighborhoods and rural pockets along the Boulder and Weld county line. The outcome of the race may determine whether Democrats keep their supermajority in the House. If they lose three House seats, they lose their supermajority.

Suddenly she was in the same boat as Harris, who had started a campaign for president a week earlier after incumbent Joe Biden stepped aside amid mounting pressure from his party.

The only difference was that Harris had 107 days, a couple hundred million dollars and a fully built campaign infrastructure inherited from President Biden. McMillan had 100 days and was starting from scratch.

The Vacancy Committee

Parenti was one of the legislature’s most progressive Democrats. When she dropped out of the race, she blamed the Capitol’s political culture, saying she could not “continue to serve while maintaining my own sense of integrity.”

“The two are simply incompatible,” she wrote in a statement, saying personal agendas and special interests had made the job too difficult.

Parenti’s exit weeks after winning her primary this year forced a Democratic vacancy committee of 34 party insiders from the district to convene to select a new candidate. McMillan was determined to speak to every member of the committee.

Immediately, she started sending group texts and cold calling members of the vacancy committee. Then, she threw on a pair of running shoes and started knocking on their doors. That decision would result in meaningful conversations — and a dog bite.

“There was a gate [to a house] that said, ‘Dogs on premises, keep the gate closed.’ And I was like, ‘OK, I can handle a dog,’” McMillan said. “I did not read the third line of the sign that said, ‘Do not enter without permission of owners.’”

Her daughter had seen the sign but didn’t think it was something important enough to mention. So, when McMillan rang the doorbell, she quickly learned why the sign was posted; two very large pit bulls came running out of a very large dog door.

“At first I thought, ‘OK, I’ll just put my hand out for them [to smell].’ But no, they were just, like, barking and jumping and my shoes fell off and they bit me really, really badly,” McMillan said.

All of those efforts would leave her with a torn-up pair of pants, some massive bruising and yes, the Democratic nomination for State House District 19.

McMillan narrowly won the vacancy committee vote on Aug. 8 in the second round of voting, 16-14. She defeated three other candidates, two of whom were former elected officials.

She now faces former state Rep. Dan Woog, an Erie Republican, in the general election. Parenti beat Woog in 2022 by 1,467 votes, or 3 percentage points, in a district whose voters have traditionally favored Republicans. Now, Woog is battling to reclaim his spot in the legislature.

“I truly was pretty certain I wasn’t going to do it,” Woog said of running again. “I’ve just had constituents reach out and say, ‘Hey, look, it was this close. We’d love you to do it again.’”

The Woog campaign strategy

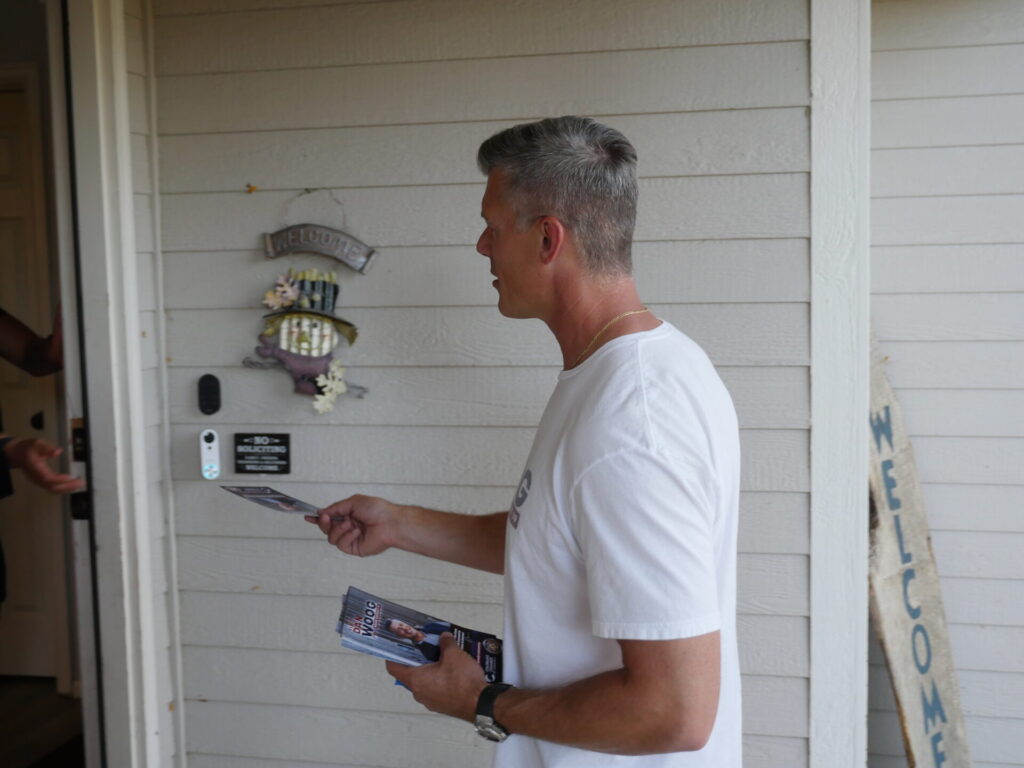

Former Colorado Rep. Dan Woog speaks with a Republican voter at their door Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Longmont. Woog previously represented the area but was defeated in 2022. He is now running for his old seat. (Lincoln Roch, Special to The Colorado Sun)

Woog announced he would run for his old seat in September 2023. This is his sixth time running for office. Three of those bids were for Erie town trustee, where he lost his first race.

All that campaign experience has taught Woog the importance of retail politics. He started knocking on doors in April and has hit 9,600 houses since with the help of volunteers. His strategy revolves around letting his talking points take a back seat to what voters have to say.

“I have my platform, but the reality is, I’m only gonna be better if I listen,” Woog said.

A valuable lesson from his failed 2022 statehouse bid was that he needed to learn more from the unaffiliated voters in the district and even some Democratic voters. From conversations with those voters he’s started talking about something not usually associated with conservative politics: the environment.

The oil and gas industry is prominent in his district. In the past, Woog has been a supporter of the industry. But after conversations with voters, he now has some concerns.

“There’s so many people in Erie that are even conservative or fiscally conservative, they’re independent voters, and they are worried about the environment,” he said. “They’re worried about oil and gas and the effects it has on our air quality. This has to be a focus.”

While Woog still believes in the importance of oil and gas — he says his first statehouse campaign was driven by what he saw as an attack on the industry — he said he now recognizes the need for alternative energy sources. He specifically wants to advocate for solar power and nuclear energy if he returns to the Capitol.

While McMillan has benefited from the help of major Democratic figures in the state — including both of Colorado’s U.S. senators, U.S. Rep. Joe Neguse and Attorney General Phil Wieser — Woog has not seen much support from the Colorado GOP. He thinks they may have sent out an email supporting him, but that’s it.

The party has been in turmoil for months under the leadership of embattled Chairman Dave Williams. Woog has stayed out of the drama, which he thinks has served as a distraction given the upcoming election.

“It’s frustrating as a Republican,” he said. “I told myself, ‘I’m just running my race.’”

89 days out

The formula to win a campaign has a long list of components. Logan Davis, a political consultant and the former deputy director of the Colorado House Majority Project, knows that formula very well.

He explained that the most crucial thing McMillan needs is for voters to simply know who she is. To do that the campaign needed to create ads, recruit volunteers and then get those volunteers to knock on doors, put up yard signs and hand out literature.

To buy all those ads, signs and literature, you need money. To recruit and manage those volunteers, you need a volunteer coordinator, which costs money. And to travel around a spread-out suburban district you need gas, which costs money. So step one for McMillan? Gather lots of it.

Woog, the representative Parenti beat in 2022 and McMillan’s current opponent had the clear fundraising advantage. He’s raised over $100,000

On Aug. 1 while she was still competing for the nomination, Woog had $36,678 in cash on hand. Davis says that money doesn’t make or break a campaign, but it can make winning way easier.

“The less money you have, the more physical labor you have to do, the more doors you have to knock, the more people you have to call to get your name to spread as far,” Davis said. “People are probably going to burn through some pairs of tennis shoes in attempts to get the job done.”

McMillan lent the campaign $20,100 of her own money and started fundraising.

As of Sept. 30, the McMillan campaign had $39,060 on hand from 285 unique contributors compared to Woog’s $63,241. The McMillan campaign shared their unique contributor data from Act Blue, a Democratic fundraising platform, for this story.

“When I got my first large donation, I got teary because it was from a good friend. And I just was like, ‘Yea, somebody believes in me,’” McMillan said.

But with no campaign experience, she needed somebody who knew how to run a campaign. She needed someone who could work as hard if not harder than her. She needed a campaign manager, which she quickly found in Reilly Jackson.

45 days out

Democrat Jillare McMillan talks to a couple inside their house Saturday, Sept. 28, 2024, in Erie. McMillan entered the House District 19 race in August after incumbent Colorado Rep. Jennifer Parenti, D-Erie, dropped out of the race. (Lincoln Roch, Special to The Colorado Sun)

It’s 9 a.m. in Frederick and there are 45 days until Election Day. The annual Miners Day parade starts in one hour. The McMillans’ minivan is nestled between a dance troupe practicing its moves and a float with signs encouraging people to vote. Her van is decked out in campaign signs that arrived 16 days earlier and a bubble machine strapped on the roof. The only problem: Now the van won’t start.

That’s when 20-year-old Reilly Jackson, McMillan’s campaign manager, walked up. Jackson was carrying handmade signs she’d made the night before. The University of Colorado political science major immediately started rounding up volunteers so McMillan could focus on the pressing matter — getting that van rolling, which McMillan did.

A lifelong resident of Erie, the biggest town in House District 19, Jackson has been engaged in politics since she was 12. At 18 she interned for Neguse and spent this summer interning for Polis. McMillan had eagerly reached out to Jackson after Parenti recommended her, and the women quickly hit it off.

“We realized that there’s a lot of mutual crossover, and not only where we are ideologically, but also the motivations we have for the district,” Jackson said.

However, Jackson isn’t a bored student looking for something to do in her free time. Between the campaign, her social sorority, five classes and professional fraternity, she’s clocking 65-hour work weeks until Election Day.

“I do think we can win it, but it’s like, Tim Walz says, ‘You’ll sleep when you’re dead,’” Jackson said, referring to the Minnesota governor who is Vice President Kamala Harris’ running mate on the presidential ticket this year. “So that’s where we’re at right now.”

38 days out

It’s 86 degrees and sunny at Erie’s community park as the cheers from Sunday morning soccer and baseball games fill the surrounding neighborhood. A few blocks away from the cheers and orange slices McMillan is wrapping up a six-minute conversation with a voter in their doorway. As she leaves the driveway she records a few notes on her phone using speech to text.

“He was a registered Democrat for a long time and is unaffiliated because he doesn’t like the partisanship and [there’s] too much government overreach on some things,” McMillan said.

Then she starts walking to her next stop five doors down.

The more technical term for this is canvassing and while it seems as simple as the candidate or volunteers going from door to door, it’s a bit more complicated.

The campaign uses an app called Votebuilder which organizes public voter registration data and allows the campaign to determine, among other things, what political party a homeowner is a part of. Because the campaign has so little time, they primarily focus on unaffiliated votes since that voter block will likely decide the election.

Logan Davis, a democratic political consultant and the former deputy director of the Colorado House Majority Project, calls canvassing the building block of local politics. He explained that while we are accustomed to seeing national politicians on the news essentially as television characters, local candidates don’t have the luxury of name recognition.

“You have to get out there and convince people that you are a real person of real substance and that you have what it takes to represent them,” Davis said. “Showing up on their door and letting them hit you with questions tends to be a really powerful way to do that.”

When McMillan is going door to door to talk with voters, she always starts off the conversation the same way. She introduces herself as a Democrat who is a first-time candidate with a history of bipartisan political work. Then instead of going into her positions or plans, she asks the voters what issues are most important to them.

While topics are often different at each house, McMillan consistently finds a way to share her experience. On public education, she’s a mom of four and PTA president. On housing costs, she’s a homeowner who’s seen her insurance premiums rise. On hyper-partisanship, she has almost a decade working closely with Republicans — and she’s married to one.

While some conversations are brief, some go beyond five and sometimes 10 minutes and occasionally diverge away from politics.

At one house, a voter shared his concerns about inefficiencies in education funding. McMillan told him about a program she participated in with the St. Vrain Valley School District that invites parents to see the administrative side of schooling. By the end of the conversation, she was more focused on helping him find ways to get involved in his kids’ school than getting his vote.

As a property manager, Woog says he has seen the realities of Colorado’s housing crisis first hand.

He claims that increased regulations on businesses in the state have increased his company’s costs, and he’s had to pass those costs onto his customers. Woog says he also knows that it’s not only the rent that is going up for tenants.

“I have more tenants now that aren’t paying their water bills in time,” he said. “I see more yards dying as I do HOA drive-throughs. People are struggling, there’s just no question.”

He blames Democratic control of state government for the tough times.

“The laws in the last few years forced me to hire more employees to meet compliance needs,” he said at a rally in Thornton earlier this month. “My liability has gone way up.”

Woog sees condominiums as part of the housing solution in Colorado.

New apartment construction has outpaced condo buildings since 2008 in Colorado. A failed bill at the Capitol this year attempted to boost condo construction by limiting the powers of homeowners to file lawsuits over construction errors. Woog, a single father of two, thinks reducing developers’ liability could spur construction and give younger generations the ability to buy starter homes.

“That’s just one thing that’s going to allow, hopefully, my kids to actually afford to live here — having condominiums again,” Woog said.

If elected, Woog said he also wants to revive a bill he introduced in 2022 that would provide renters with an income tax deduction. A similar measure failed at the Capitol this year.

34 Days out

Before the children leave for school and campaigning starts for the day, the McMillans have a family prayer. As a devoted member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, McMillan attends church every Sunday, volunteers for her congregation, has a daughter on a mission trip and doesn’t work on the Sabbath.

It’s often a shock when people hear she’s endorsed by Planned Parenthood. But while the church is often associated with conservatism, McMillan says its teachings have led her to support progressive policies.

On the topic of abortion, she said the church teaches her to honor life and that she has a responsibility to take care of others. It also emphasizes individual choice and allows for free agency. She doesn’t think those teachings are incompatible.

“There is that misconception out there that ‘you’re a Mormon, your church says you can’t ever do this,’ and that’s actually not true,” McMillan said. “I essentially feel like this is a decision that should be made by a woman, and that she can counsel as she chooses, with her partner, with her doctor and if applicable, her God.”

With four kids who grew up in a world filled with mass shootings, she’s an advocate for tougher gun regulations. McMillan is endorsed by Moms Demand Action, Colorado Ceasefire and Sully’s Action Fund, which is linked to state Sen. Tom Sullivan, a Centennial Democrat whose son was murdered in the 2012 Aurora theater shooting.

“They’ve experienced active shooter drills for most of their school lives,” McMillan said of her kids. “I was in a kindergarten classroom many years ago during an active shooter drill. It’s scary, and it’s scary for kids.”

After her kids leave she heads to the campaign office, a former dining room she shares with the family rabbit, Snickerdoodle, opens her computer and gets to work.

By the time they return around 3:30 p.m., she’s had four video calls, sent dozens of emails and text messages and met with a labor union whose endorsement she’s seeking. She’s also gone on a run, done some laundry, taken care of the payroll for her husband’s small business and debated him over the contentious issue of Papa Murphy’s versus Costco pizza for dinner. [CP1]

But as they walk in from school, she closes her computer and asks about their days, something she always looks forward to. The conversations tend to be brief.

“They’re not very chatty. They’re teenagers right now,” McMillan said.

She’s told her kids that they can only have pizza if they man the phones or clean up the house before the volunteers arrive for a phone banking event that night.

7 Days out

Former Colorado Rep. Dan Woog, R-Erire, speaks with a supporter before the Frederick Miners Day Parade Saturday Sept. 20, 2024. Woog previously represented the area but was defeated in 2022. He is now running for his old seat. (Lincoln Roch, Special to The Colorado Sun)

The reality is that after all of Woog and McMillans work, external factors may end up deciding the race. Almost all of HD-19 is in Colorado’s eighth congressional district, one of the most competitive races nationally, which could decide control of the House of Representatives. This has resulted in millions of dollars flooding into that race.

Winning the purple district’s conservative towns that HD-19 encompasses will be crucial for Republican State Rep. Gabe Evans’ chances of flipping the seat. Davis said whichever party wins CD-8 will win HD-19, which he thinks could be an advantage to McMillan.

“If I were Jillaire McMillan, that would be my favorite thing right now. There is an incredibly hard-fought national race, getting a lot of national attention, pouring millions of dollars into the area where I’m running, you can’t really buy that,” Davis said.

But with CD-8 polls showing the race neck and neck, the margins in HD-19 could be even closer than in 2022. It’s not uncommon for some competitive state house races to be decided by hundreds of votes.

Woog has significant name and fundraising advantages. McMillan and Jackson know they’re waging an uphill battle. If anything, it pushed them harder, like a football team going into the fourth quarter behind, still determined to win.

“I really feel like I can win,” McMillan said. “I’m not a career politician. I’m a regular person who just cares a lot. I think that there’s something about that, that that people are really going to find appealing.”

Now as the election starts to go from weeks to days away, there’s no way to know who will represent HD-19 come January. But On Nov. 5, win, lose or draw, McMillan and Jackson still built a state house campaign from the ground up.

“This is such a pressure cooker to be thrown into this race with, like, 100 days and no money at the start. That’s a crazy scenario to end up in. And if they could come out on top of that, we should make statues of them,” Davis said.

this story originally appeared at coloradosun.com