By Juanita Hurtado

Over the last year, thousands of migrants have been arriving in Denver looking for shelter and leaving behind the violence and financial strain of their homeland. But, as Denver has started to set up stricter policies, a new problem has been arising: how to provide for the newcomer students that are arriving at schools state-wide.

More than 6,000 newcomers have enrolled in Colorado schools since this summer, according to CPR. In Boulder alone, schools have started new strategies to serve 200 newcomers across the district. University Hill, a dual-language elementary school in Boulder has welcomed over 30 students this year.

We’ve accepted our students and are getting to know them, getting to know their families,” stated Marina Orozco-Ngu, University Hill’s principal. “We had a newcomer dinner at the end of January where we invited families in and asked them questions: What do they expect of their new school? If they could create their ideal school, what would it be?”

This newcomer dinner is one of the latest additions to University Hill’s newcomer program. At the beginning of the year, their first newcomer dinner served as a way to explain to parents the way the school worked compared to the education systems in their homelands: longer hours, instruction in Spanish for half of the day and in English the other half, as well as provided help connect parents with BVSD’s family resource services.

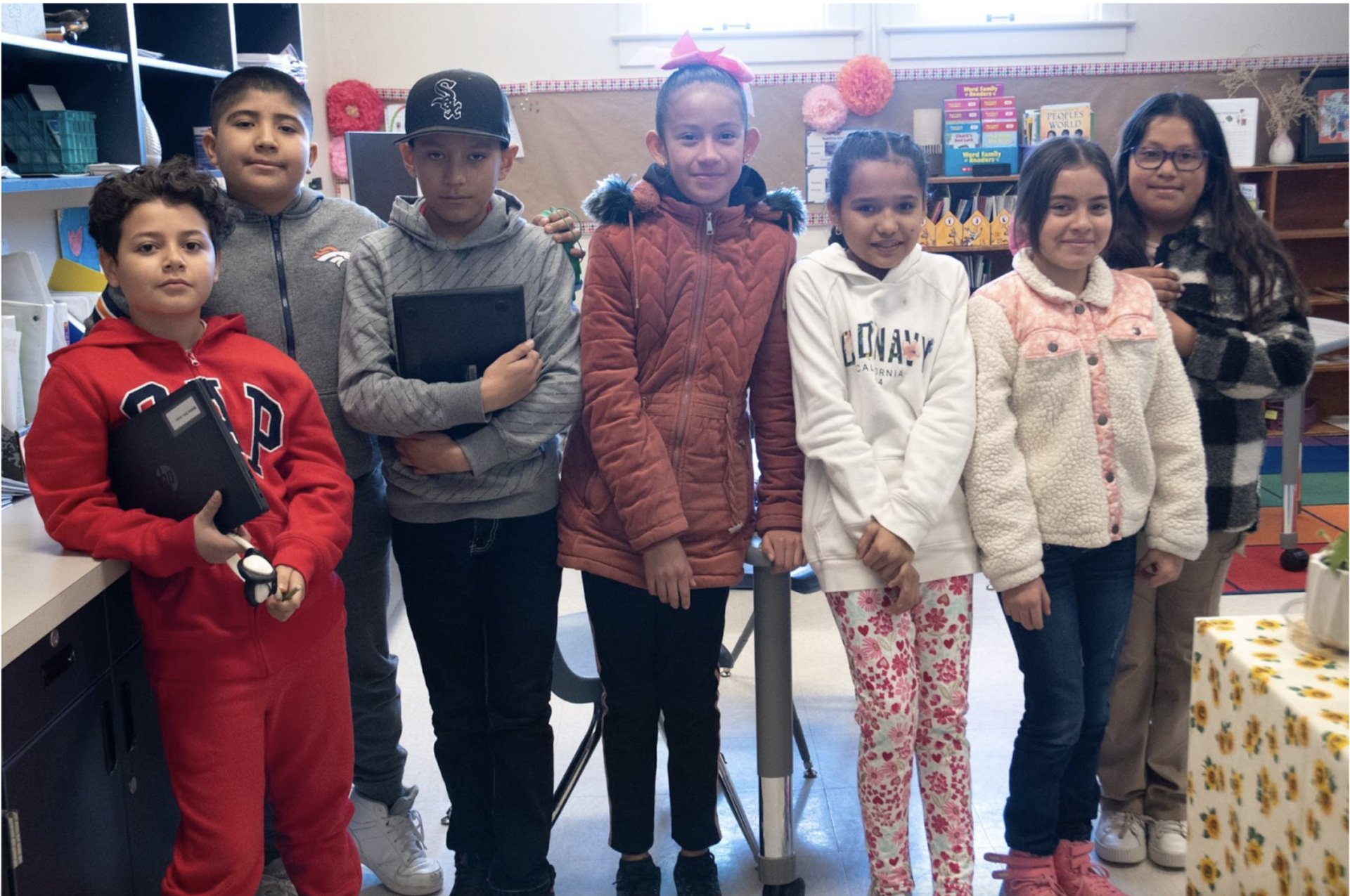

Among their services, University Hill also provides co-teaching strategies with English language development teachers coming into classrooms to support the kids’ learning; the Welcome Club, where kids can stay after school to strengthen their skills through play–baking cookies to reinforce their knowledge of numbers and measurements, tie-dye to talk about colors– and have a support network while they build up the confidence to make other friends.

Newcomers at University Hill aren’t grouped together as other schools might do. Instead they are spread out in different classes and then pulled out throughout the day into a small group where ELD teachers Lisa Hammond and Ashley Owen help them work through questions about their classes, English, or this new environment.

“Our whole goal in doing the pull-out newcomer group is to give them targeted instruction at their level.” said Lisa Hammond, ELD teacher at University Hill. “They also get support in the classroom during their regular English time, but being able to have this targeted support where they’re learning not just the academic language, but the basic social language that they need in order to survive on a daily basis.”

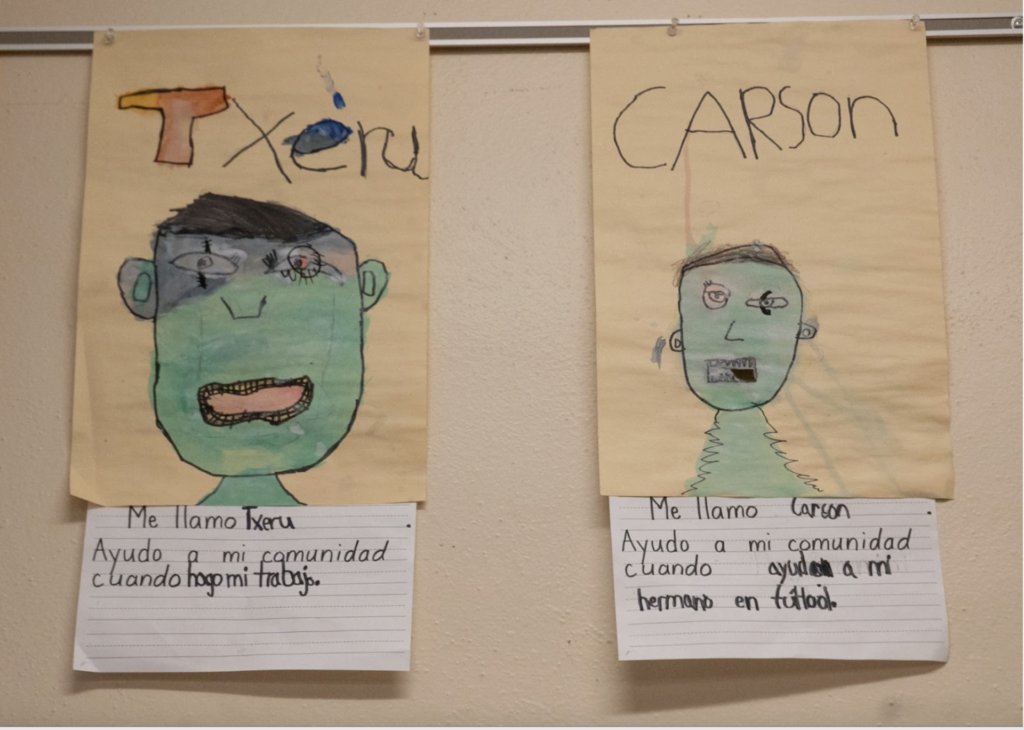

Arriving in a new country presents a lot of challenges. A fear of being ostracized or not welcomed, cultural shocks, and the uncertainty of not being able to communicate with peers and teachers, make friends, or even work on academic learning. University Hill’s bilingual staff takes away this uncertainty, bridges the language barrier, and provides a space where newcomers can learn the survival language while knowing in case of an emergency or when they don’t have enough vocabulary to express themselves yet every teacher at school will be able to understand them.

“[Our] main focus is to make them feel welcome,” stated Ashley Owen, ELD teacher at University Hill. “Allow them to be able to take the risks that they need to take to be able to learn a new language and to feel comfortable in the atmosphere to take those risks. One of the first things I think we both {Lisa and Ashley] tackle is helping them to learn important questions that they need to ask at school, just like can I go to the bathroom? Can I go to the nurse? Things like that. Survival.”

Many of these newcomers have also experienced deep trauma, from leaving behind situations of violence to the dangers of crossing the border, and in some cases even backgrounds of interrupted education. According to Hammond, these factors can make the assimilation process more difficult. A kid struggling with feeling safe or with having their emotional needs met and not having a strong education base can’t concentrate at first.

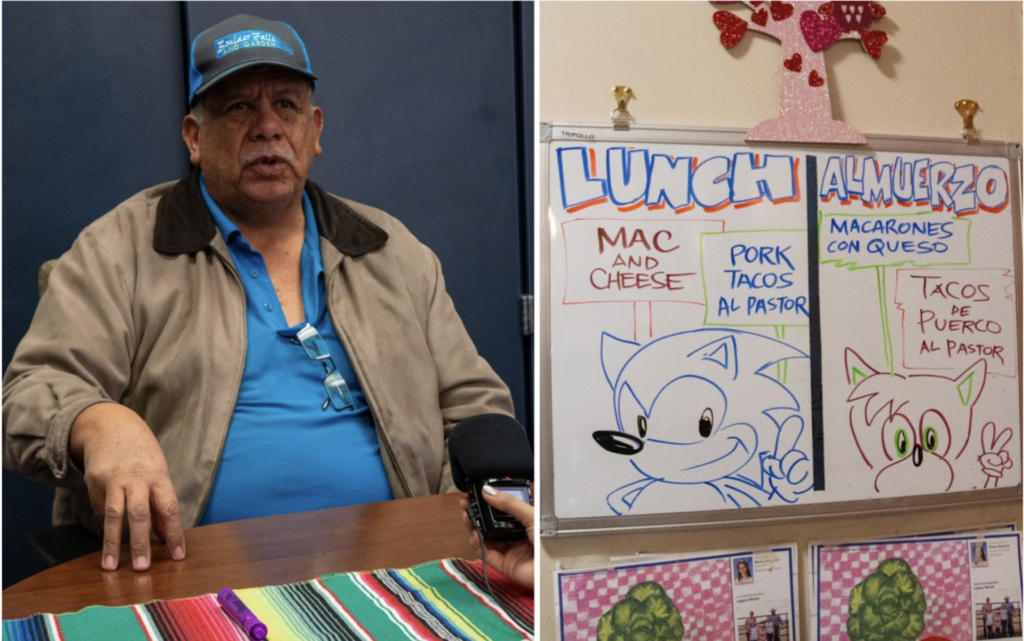

“[People] need to know these kids need all support they can receive. It is hard for them to come from places where life is in danger and they cannot play or do other things kids do and then adapt to a place where you can feel welcomed,” said Raul Aguilar, the grandfather of a newcomer at University Hill. “One of the questions he had [his 10-year-old grandson] was that when we told him he was taking the truck, the bus, he asked: what if they kidnap me?”

Aguilar also emphasized the need for the general public to recognize the hard work teachers are doing to welcome these new students. From providing the welcome club, newcomer dinner, and pull-out groups to creating relationships with their kids aiming to meet each student’s academic and emotional needs. All information from University Hill is also provided in both English and Spanish.

One of the challenges schools have faced is that the public funding they receive for these newcomers depends on a survey that needs to be filled out by October for the Colorado Department of Education. Therefore, any students arriving after that deadline are not taken into account for schools to get funding. The Colorado Department of Education and different school districts are strategizing new ways to provide for the schools.

The school’s PTO has also donated winter outerwear for the newcomers’ families and gift cards for teachers to purchase school supplies.“ Our kids deserve to be part of a program that honors their story, that honors their experiences,” Orozco-Ngu remarked. “A lot of times, you know, we hear from parents that that’s why they choose this school because halfway through the day, the student is in their dominant language, and so that’s to their advantage, right, that they can use our program model in that way.”