By William Flockton

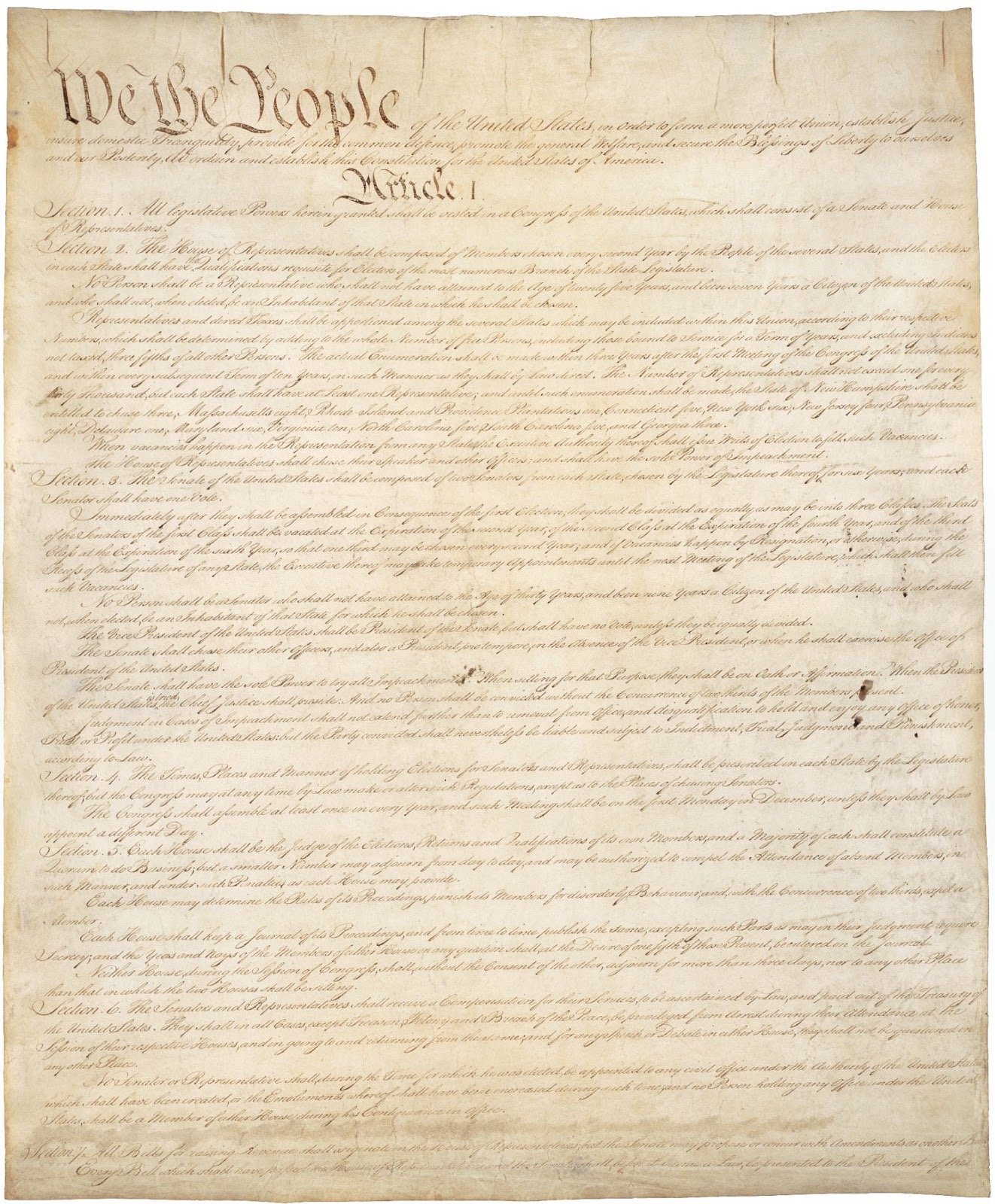

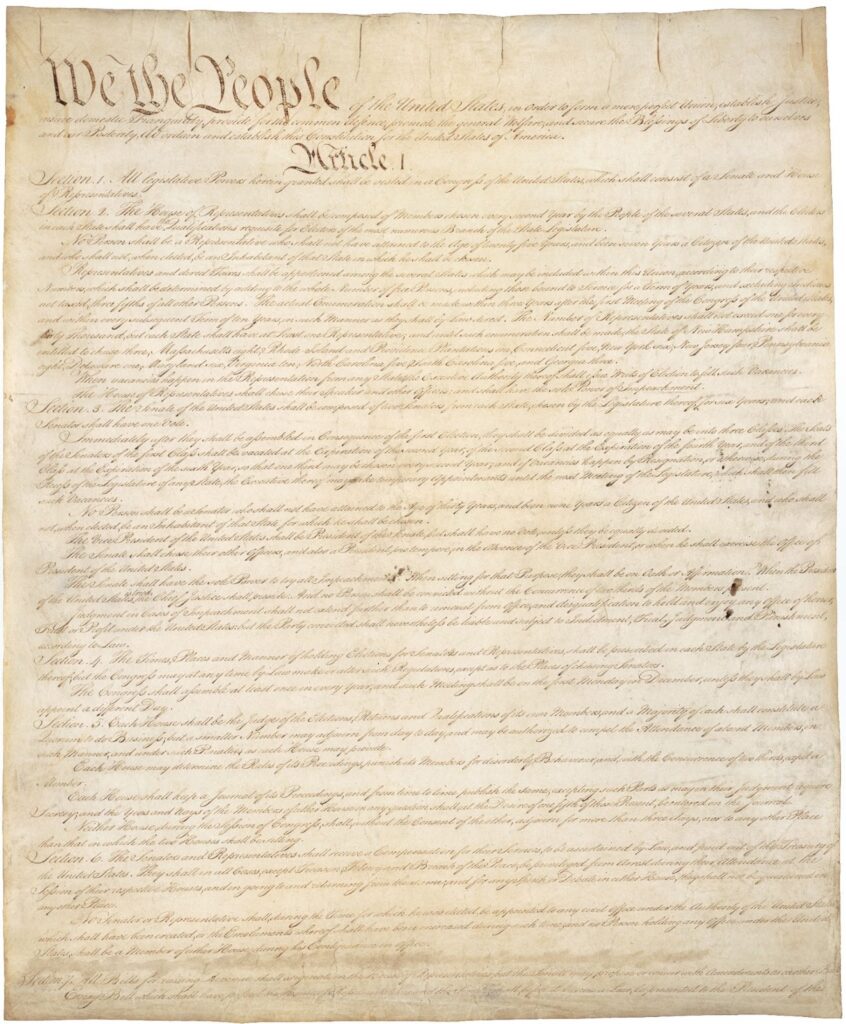

Before its ratification, the Constitution was translated into Dutch and German for the citizens of the United States of America. These translations serve as a link to the multilinguism intertwined in America’s past and language. Photo Courtesy National Archives.

What makes someone truly American? Is it being born in the US, participating in American culture, being Christian or speaking American English?

According to Pew Research Center, language is the most important part of national identity. In a 2023-2024 survey, Americans ranked being able to speak English as the most important aspect of being American.

It ranked above being born in the country, sharing the US’ customs and traditions or being christian.

Despite the importance Americans assigned to it, English wasn’t the official national language until this year.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order in March to designate English as the “one – and only one – official language” of the United States. President Trump argued that it would promote unity and a shared American culture. Critics say that it erases an even older American legacy of multilingualism.

The US’ multilingual history traces back to the nation’s founding. Before it was ratified, the US Constitution was translated for the German- and Dutch-speaking populations of Pennsylvania and New York into their respective languages.

However, multilingualism’s impact on the US reaches beyond its Constitution. In fact it has marked the very language most Americans speak every day.

It is no secret that the English modern Americans use every day is not the same English that the British first brought to the colonies. Geographical isolation from Britain, the evolution of dialect and the influence of immigrant and indigenous language shaped American English for centuries.

But what does American English say about American culture? And what specifically makes American English different from the English spoken in the UK?

In 1919, these questions drove American editor and critic H.L. Mencken to write “The American Language; An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States.” Mencken was intrigued by the differences in the English of Americans and the British, but could not find an official book which discussed what made American English so different. Thus Mencken set out to write, in his words, the “first sketch of the living speech of These States.”

Mencken noted that one of the chief characteristics of the American language was “its impatient disdain of rule and precedent” which allowed it to more easily adopt new words and phrases.

“American thus shows its character in a constant experimentation, a wide hospitality to novelty, a steady reaching out for new and vivid forms,” Mencken wrote. “No other tongue of modern times admits foreign words and phrases more readily; none is more careless of precedents; none shows a greater fecundity and originality of fancy.”

The American language’s attraction to foreign words and phrases might be best demonstrated in a few of the US’s regional dialects, which PBS explored in its 2005 documentary “Do You Speak American?”

Many dialects like Cajun and Chicano combine the vocabularies of English with other languages. Cajun borrows from French vocabulary like cher or uses phrases like “making groceries.” Meanwhile, Chicano combines the vocabularies of Spanish and English into “Spanglish.”

But influences from other languages go beyond dialects heavily influenced by any one culture.

Mencken was one of the first to highlight that words and phrases adopted from languages other than English have always been considered Americanisms: words or phrases tied to American culture. Several common words within American English come from other languages, with boss coming from the Dutch and agenda from Latin.

Today, multilingualism isn’t limited to American English alone, but extends to the vast number of bilingual US citizens.

According to a Census Bureau report published in June, one-in-five people residing in the US spoke a language other than English at home, and 62% of those individuals were able to speak English “very well” according to the bureau’s surveying.

Multilingualism is reflected in the US’ English and history. But does President Trump’s order actually celebrate it?

The order calls for the repeal of Executive Order 13166 of August 11, 2020–a Clinton-era executive order which required federal agencies and services to be accessible to individuals with limited English proficiency. While President Trump’s executive order doesn’t prevent agencies from continuing to provide accessibility to individuals with limited English proficiency, it no longer requires them to provide it.

Though it is not written in the Constitution, the Founding Fathers decided it was important enough for the Dutch and German speakers to read the Constitution in their native language.

What does limiting the accessibility of government documents and communication for non-English speakers celebrate? Closing a door on the influence other languages have on American English by limiting their use in government business? The US’ multilingual history which gave birth to American English?

And what makes American English American? Is it solely because it is used by Americans or because it was created by the immigrants who came to America seeking new freedom and opportunity?