By Nicholas Merl

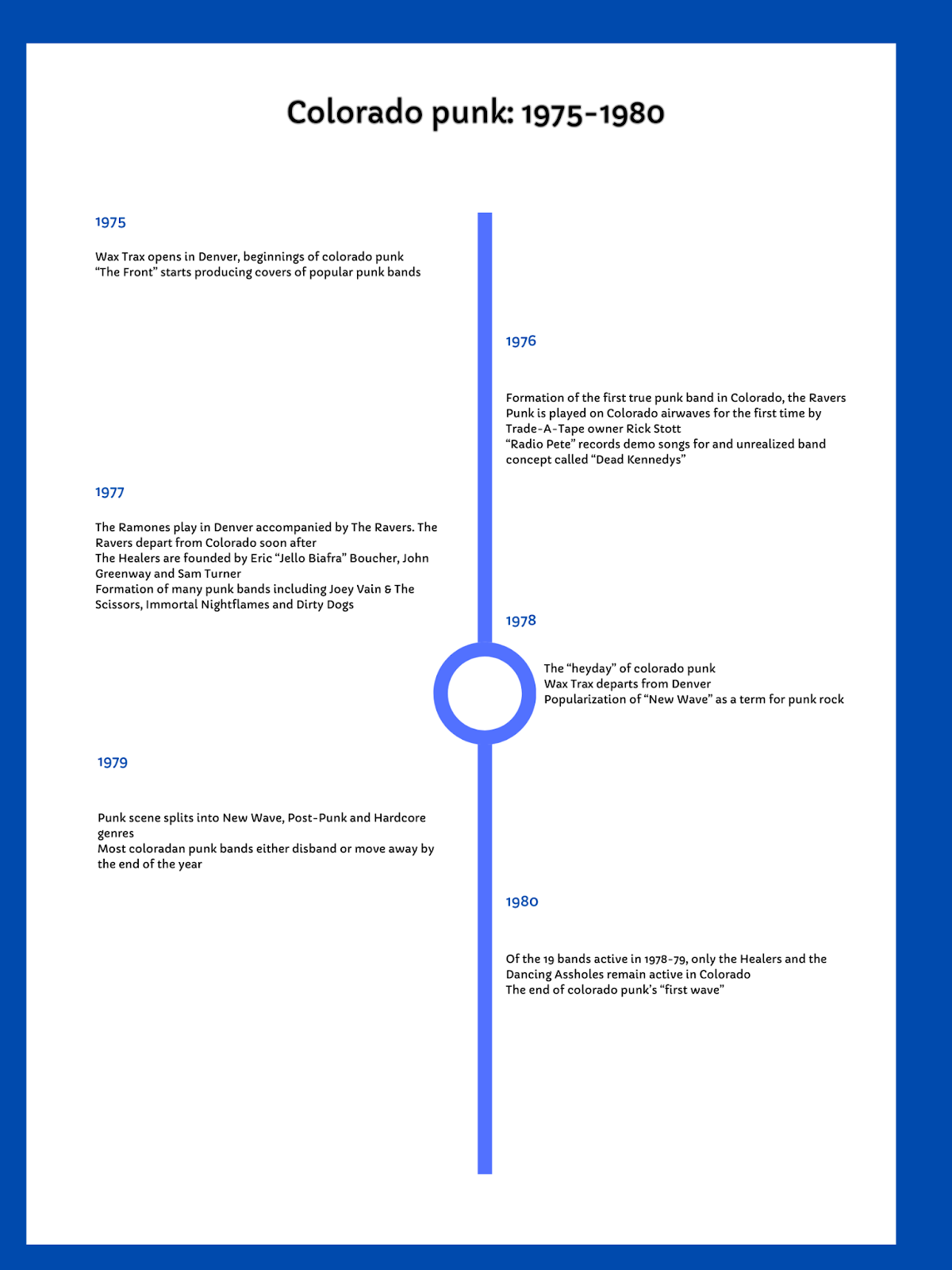

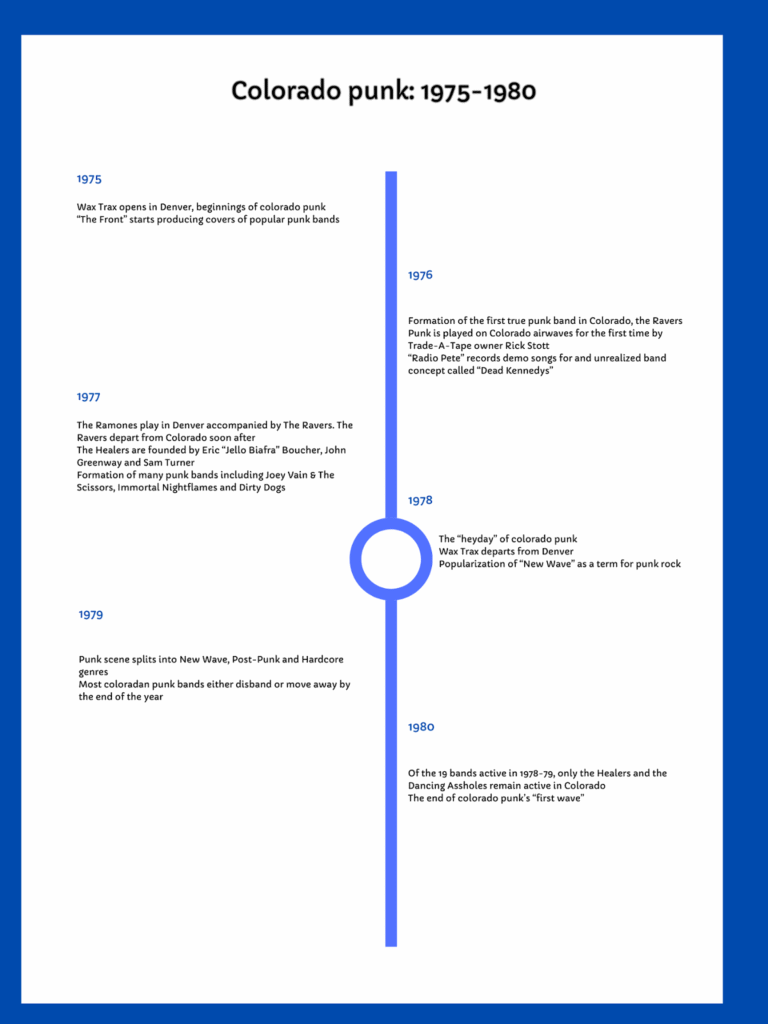

A timeline of Colorado’s “first wave” of punk rock artists. (Nicholas Merl/Radio 1190)

Colorado is home to an incredibly vibrant and diverse musical underground with a rich history. Throughout the late 1970s and early 80s this scene, largely localized in Denver and Boulder, hosted a small but active niche of punk rock enthusiasts. A small number of bands and musicians with names like the Defex, Profalactics, The Ravers and others sustained a brief but prolific outburst of creativity. And while this first wave would largely sputter out by 1979, many of its members would go on to participate in and influence punk rock around the country. The oft-forgotten early history of punk rock is, in many ways, encapsulated by the activities of Colorado’s early scene.

Of course, punk was not always endemic to Colorado. From its beginnings in New York in the early-to-mid 1970s, punk quickly swept big cities from Boston to Los Angeles to London. However, especially prior to the 1980s, American punk was a coastal phenomenon. The early Colorado scene which began to emerge in 1975 and 1976 was much smaller, and largely localized around two record stores: Wax Trax in Denver and Trade-A-Tape in Boulder.

Wax Trax can arguably be credited for introducing punk rock to Colorado. Opened in December 1975 by Arkansas transplants Jim Nash and Dannie Flesher, Wax Trax sold records from emergent bands like the Sex Pistols, the Ramones and others. The new music quickly garnered enthusiasm among Colorado’s musical underground, inspiring a few early imitators and cover bands.

By comparison, Trade-A-Tape had a more active influence on the development of punk in Colorado. Trade-A-Tape acted as a rehearsal and gathering spot for many early punks. Its owner, Rick Stott, acted as a manager to Colorado’s first actual punk band, The Ravers, formed in early 1976. Stott would also go on to be one of the first people to play punk on Colorado’s airwaves later in 1976. Together, Wax Trax and Trade-A-Tape acted as significant catalysts for the Colorado punk scene.

The Ravers’ formation was the second pivotal moment for the small but growing punk community. “ They were the first band that was calling themselves a punk band in Colorado,” Dalton Rasmussen, co-creator of the 2009 compilation “Rocky Mountain Low: The Colorado Musical Underground of the Late 70s,” said. The group recorded their first EP in Boulder in 1977 before rebranding to “The Nails” and moving to New York later that year, where they would go on to reach limited acclaim with their 1981 song “88 lines about 44 women.”

Nonetheless, The Ravers’ particular style quickly caught on. Local musician “Radio Pete” began writing songs in 1976 for a concept band called “Dead Kennedys.” Somewhat ironically a young Eric Boucher, who would later be known as “Jello Biafra” of the “actual” Dead Kennedys, formed the band “the Healers” with his childhood friends John Greenway and Sam Turner in Boulder in 1977. Other bands formed in 1977 included Joey Vain & The Scissors, Immortal Nightflames and Dirty Dogs. By early 1978, Colorado’s punk scene was in full bloom.

While the early scene that developed around and in the aftermath of The Ravers’ time in Colorado was incredibly close-knit, it was stylistically incredibly heterodox. The Ravers themselves had initially formed as a reggae band, and even after they adopted the punk moniker, it didn’t catch on with everyone in the musical underground. “Punk is such a dirty word for me,” Joel Haertling, an art collector and childhood acquaintance of many prominent underground musicians from Boulder, said. “We didn’t always call ourselves punks.”

At the same time, Punk was gradually splitting into separate categories and labels. Many of the more artsy musicians started to associate themselves with embryonic post-punk and prog. The most clean-cut and photogenic members of the underground would initiate the iconic “New Wave” of the 80s, while the traditionalists rejected this in favor of pure, aggressive Hardcore. However in 1978, many of these terms were either nonexistent or effectively synonymous. Colorado’s early scene was especially shaped by this diversity.

“ If you went to a punk show, you would maybe have some of a hardcore band playing with a noise band, playing with a performance artist,” Bob “Bob Rob” Medina, a former musician and show organizer in Denver, said. “It all kind of fit into this punk category. Anything that was weird was punk.”

The Colorado scene’s sound was equally distinctive, partly owing to a lack of refinement but also a distance from the coastal nuclei of punk rock. “ Denver was kind of really on its own trajectory. It just, it didn’t have something to model what punk was really,“ Medina said. Much of the music produced between 1976 and 1981 became progressively more experimental. This was partly tied to national trends in punk rock, but partly an organic development. “A lot of the music had been changing and there was a lot more experimental stuff coming out in 78 and 79,” Rasmussen said. “ I actually think that’s a bigger thing that I hear about Colorado art in general, that sometimes,” Stephanie Wolf, a Denver-based journalist who has researched the early punk scene, said. “Artists here feel completely unbound by the trends that are happening in New York and L.A. Or New York and San Francisco.“

One thing Colorado’s scene did share with punk nationally was an enthusiasm for everything crass and offensive. Bands such as Jonny III plastered swastikas across their album covers while the Healers used pictures of Auschwitz victims on theirs. The nazi imagery was as widespread as it was unserious. “Back then it was about pissing off your parents who’d lived through world war 2,” Haertling said.

At the same time, punk was a hotbed of sincerely progressive – and sometimes transgressive – politics. Colorado was no exception, with bands like the all-female Profalactics making heavy use of feminist imagery and themes in their music, while the aforementioned Dancing Assholes committed themselves heavily to anarcho-syndicalism. The over-the-top offensiveness and simultaneously sincere progressivism often went hand in hand. “ Our singer in my first band was openly gay,” Bob Medina said. “He used to carry a four foot doll up on stage, and he would talk about how he likes little girls and stuff like that, and had a song about little girls. That was punk. It was just crass and offensive and funny. It had a sense of humor to it.”

The “first wave” of Colorado punk ultimately came to an end in 1978-1979, although this was also its most prolific and active period. Increasingly the three main strands of punk – new wave, post-punk and hardcore – were diverging. Additionally, 1979-80 would mark a simultaneous disbanding or relocation of many of the old bands and foundation of many newer bands. Of the nearly 19 bands that had made up Colorado punk’s first wave in 1979, only two survived into 1980.

According to Dalton Rasmussen, this sudden turnover was due to several factors. “ There was a lot of change that occurred from late 1979 to in 1980. 1980 was a totally different scene. It was more Denver centric,” he said. “In 1980 there was an explosion of punk and New Wave bands here in Colorado.” Additionally, many “first generation” artists were leaving after completing college. “ Especially the Boulder bands. I would say that some of them were finishing up school. And they were like, okay, we’re done. We’re gonna move somewhere else.”

But while the Colorado punk scene ultimately proved to be short-lived, it still was a fascinating and significant place in its own right. It was a creation of the late 1970s – the advent of neoliberalism, the collapse of social democracy and the beginnings of our modern world – all compacted into music. In the end, while it may not have etched itself in memory, it did still etch itself in the soul of its time. For that alone it is worth remembering.